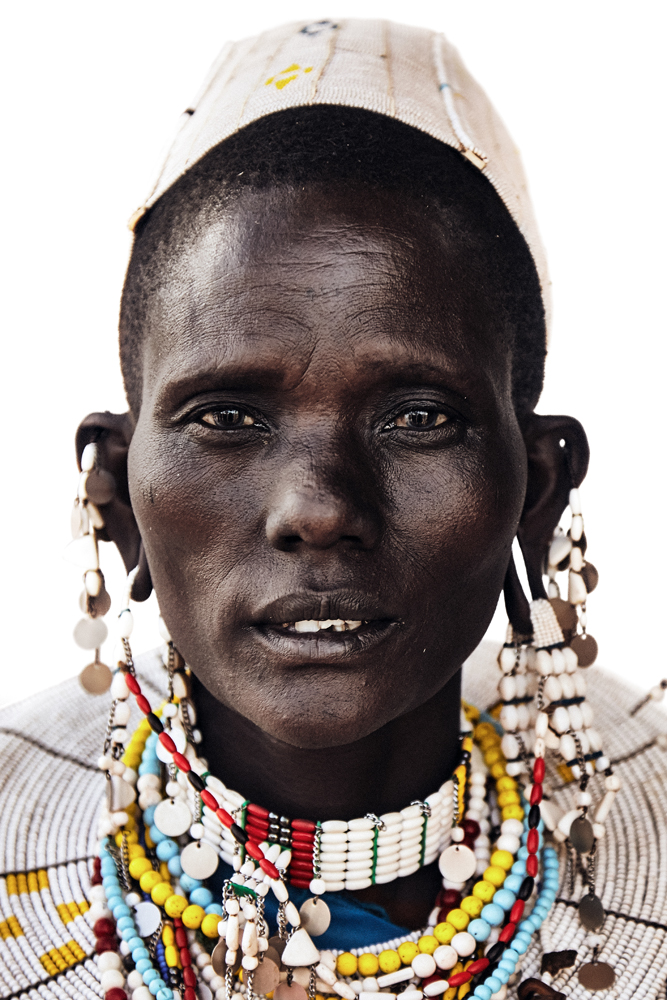

NA KISIMA (WITH THE WELL) - A MAASAI PORTRAIT SERIES

I wrote a blog post in 2015 recounting my first experience on the ground in Tanzania, Africa. At the time, I was a different person both mentally and physically. I took the time to read through that post before I started this post. As cliché as it may sound, Africa has changed me.

Prior to 2015, I had never truly ventured outside of my comfortable life. But from that year forward, I've carried a different perspective about the obstacles and amenities I have in my life.

The first trip to Tanzania was alongside Nadus Films and two time Super Bowl champion Chris Long for initiative Waterboys. Waterboys uses the platform of athletes and veterans to raise money to provide affected communities with clean, safe and sustainable water access by hiring local crews to drill deep borehole wells serving up to 7,500 people. Though I had some concept of the water crisis, it was that first trip that allowed me to really understand that the lack of access to water changes everything - from where communities pop-up, to how families grow and take care of each other, to dreams individuals have for their future.

Since that first trip, my career has taken me to the African bush every year, sometimes twice a year or more. In 2016, I documented the pre-production, and production behind a climb to the summit of Mount Kilimanjaro for Wings Of Kilimanjaro, which ultimately served the same purpose of bringing clean water to the people of Tanzania. In February of 2018, I climbed Kilimanjaro again for Waterboys, but I opted to only document the experience through a single “First Person Shooter.” While that trip provided some incredible memories I often look back on, the trip also felt like a job. It was a tough journey.

That same summer, I traveled back to the bush for a new partnership: Hoops20. Hoops20 was founded by NBA athlete Malcolm Brogdon, close friend to Chris Long. Same goal, different association. It’s always been a goal for Chris and Waterboys to expand into other professional sporting leagues such as the PGA, MLB, NHL and MLS. A highlight of that trip was sharing a day and night with PGA legend Jack Nicklaus. It was quite surreal to share a seat next to the man I watched on TV as a child.

This year, an opportunity fell into my lap - another adventure with Hoops20, along with NBA athletes Malcolm Brogdon (Indiana Pacers), Joe Harris (Brooklyn Nets) and Justin Anderson (formerly Atlanta Hawks). I had to not only provide new press photography of them, but I knew I had to do something better with the women of Tanzania, I had to do to something different, something that I had never had the time nor opportunity to do. I wanted to execute a creative vision that has been stuck in my head ever since I saw my first Maasai.

For over 500 years the Maasai culture, outfitted in their best “Shuka” and beaded jewelry, have served as the saga of the Rift Valley. The Maasai are one of the most impoverished tribes in East Africa. A noble and dignified people, they have proudly maintained their traditional lifestyle and lore despite pressures of the modern world. They live a nomadic lifestyle raising cattle and goats and living in small villages far from the more populated areas.

Maasai society is firmly patriarchal in nature, Men often have several wives and the number of cattle and children a man has measures his wealth. Women often birth as many children as possible, regardless of her health or ability to provide for them. Women rise early and spend everyday walking miles to water holes to launder clothes and gather heavy jerry cans of water to carry back home. Boys are expected to shepherd the cattle, while girls help handle most other domestic responsibilities. The Tanzanian and Kenyan governments have instituted programs to encourage the Maasai to abandon their traditional nomadic lifestyle, but the people have continued their legendary culture.

Year after year, I’m fortunate enough to visit multiple Maasai villages and meet dozens of beautiful Maasai, who are celebrating their new clean water well. While I don’t speak Swahili or the local Maa slang, I’m always able to connect through their warm smile. The christening of every new well is met with Maasai - dressed in their best clothing and jewelry - welcoming us with their traditional song and dance in large groups separated by gender. Women are often reserved or in the shadow. They don’t like to be photographed, while the men are the opposite. They gravitate towards the camera and like to be the star of the show.

I’ve always wanted to photograph a single portrait of as many women as possible in a single area on a single background. I’ve photographed dozens of Maasai, but nothing to compared to this level of control, I ultimately wanted. It was important that I didn’t force an idea or force an expression. It was important that the person translating my direction didn’t force the women to be photographed. I wanted to photograph their faces however they wanted to be captured. Privately, quiet and without the oversight of Maaasi men or an intimating production.

After an incredible few days in the Seregenti and one very nerve wracking puddle jump, we headed to a very remote part of Tanzania to visit a freshly built water well by Hoops20. The Osinoni village has a population of 3,579 people and a total of 31,360 livestock, but the entire village doesn’t have a single clean source of water, until now. Before the Hoops20 water well, the villagers had to dig small holes in the ravines to get water for themselves and their livestock.

On the way to the Osinoni village, I recruited my friend David Bongiorno of Worldserve International and one of his employees Asaph to help with some translation and engage Masai women on my behalf. While I knew basic Swahili commands, often Maasai have their own slang version and many don’t understand common Swahili, so it was important to recruit someone that could help in basic direction. I explained specifically what I wanted to do and how I planned to do it. Luckily, David was on board and loved the idea.

Upon arrival, the atmosphere is always chaotic but the energy is euphoric. I didn’t know exactly when I would have the chance to setup and start the portrait process, I had to improvise when the time was right. But, having experience I knew there would be downtime during the ceremony to hear from local leaders and government. On occasion these ceremonies are 30 minutes, sometimes they are 10 minutes. Fortunately, I had a sidekick Thomas Ingersoll, who could cover the important ceremonial down time, while I was knocking out the project.

It’s always an incredible experience to see athletes experience a ceremony such as this for the very first time. While I see it all through a lens, the power of the moment causes me to pause for a quick breath before moving onto the next moment.

The song and dance had come to an end, the ribbon was cut and all the formal photography had been captured. As the ceremony began to take place, Thomas was on it and I began scouting for an area to setup a background.

My background of choice was a Westcott Illuminator Collapsible 6-in-1 Reflector, White. I elected to do a clean white background for ultimate contrast with the dark Maasai skin color and to avoid any possible distractions from the face. I would not be using a artificial source of light, because I wanted it to be as low-impact and I didn’t want the Maasai to feel overwhelmed by the production-level that strobes would introduce. It would likely be disarming for them to have a camera pointed at them. With that said, I needed an are with a lot of light. My first idea was under a tree, but I couldn’t find a tree close enough to the ceremony site that would give me complete shade and place to hang white reflector.

I moved into the fenced well-site and noticed a pipe to the underside of the well. I grabbed an A-clamp and clamped the background to a pipe on the lateral side of the concrete base of the water tank. The issue was the background needed to be on a solid wall, since the white fabric was translucent and sun through the fabric would completely throw off exposure. Also, cloud cover was diffusing the sun randomly, so I knew this would be one of the only spots in the open with consist light. I grabbed a wooden hand-made ladder an pinned it against the wall, which held the white reflector in place. It wasn’t pretty, but it worked.

Fortunately, I had a male test subject who I’ll call the “Gatekeeper” who was helping me through this process while David and Asaph gathered a crowd of women to be photographed. I call him the “Gatekeeper,” because he actually held the key and let me into the well fence line to scout the wall under the well.

As I photographed the “Gatekeeper” and a few other Maasai men and boys, through body language and hand motion he figured out what I was suggesting: a straight-on shot and a side-profile shot. The reason I wanted this was to not only show the face of a person but show the body profile, shape of the wardrobe as well as any body scarification and ear stretching.

After about 2 minutes of testing, a line of women formed quickly and I escorted subject after subject in front of the white background. With some simple body language and a warm smile, I shook the hand of each subject and spent less than one minute with every person. Some women laughed, some smiled, a lot wondered as they looked into the glass of my lens. It’s very likely some had never seen a camera in their lives. It’s also very likely they really had no idea what was happening, but they trusted us and trusted the people that initially asked them to be apart of it. I wasn’t able to speak with every single person I photographed, but I believe their faces were engaging enough to tell a story.

As the last women stood in front of my lens, I noticed the ceremony crowd began to disperse. With the last few seconds I had, I finished the last portrait and broke down the setup. I returned to the truck and took a deep breath, only around 15 minutes has passed. While I wish I had more time to get to know every face I photographed and hear their story individually, I’m happy I was given the opportunity at all. As we watched the sunset on the drive into Ngorongoro Crater on the last day of our project, I had a sigh of relief and a moment of pride.

With every project such as this I learn more about myself and my love for photography. I try not to look back at the person I was before Tanzania came into my life, but look forward to the person I want to be after my next trip to Tanzania. This is Na Kisima - With The Well.

A special thank you to associate photographer Thomas Ingersoll for being there when I couldn’t. Thank you to Nicole Woodie, Chris Long, Malcolm Brogdon, Joe Harris, Justin Anderson, AnneMarie Schindler, John Bongiorno, David Bongiorno and Asaph Bimila.