IRAQ

Fear is described as a distressing emotion aroused by impending danger, evil or pain. Whether the threat is real or imagined, it is the condition of being afraid. I know we all have come to moment in our lives where we feel a wave of anxiety, panic and dread. Often, it strikes like a bullet to the chest or a ten-ton brick to the head. The only true remedy is yourself.

*Due to the sensitivity of this project some names, dates and locations have been changed in order to protect the lives of those involved.

I guess you could say I’ve always been the “black sheep” of the family. One to lean towards risk and adventure over security and comfort. I’ve always been fascinated by stories; non-fiction stories of mountains, heroes and war. Stories that are unbelievable, yet completely true. Stories that inspire and stories that impact. I once read into Operation Neptune Spear, the operation that raided the compound of Osama Bin Laden in Abbottabad, Pakistan. Also, Operation Red Wings which recounted the heroic battle of four Navy Seals in the Kunar Province of Afghanistan against an anti-coalition militia led by Ahmad Shah, an Islamic fundamentalist. But, despite the stories, I had little understanding of the Middle East; a tunnel vision shrouded with war, terrorism and a culture I did not understand. Despite the stories, the adventure had always called to see the center of conflict.

Throughout my entire life the Middle East had been a focus of war. I grew up watching Operation Desert Storm and Operation Iraqi Freedom, where the United States forces conquered Iraq Socialist, Saddam Hussein. Then on September 11, 2001, a series of four coordinated attacks killed 2,996 people and injured over 6,000 Americans. The Islamic terrorist group al-Qaeda conceded to the horrific attack, which kickstarted the “War On Terror” in Afghanistan, turning the Middle East into a region of blur. Obscured by dozens of terrorist organizations, multiple misunderstood religions, a baseless government and civil war.

In 2014, when the “Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant” otherwise known as ISIS, birthed from al-Qaeda, started making headlines, I was overwhelmed and numb to the war. I chose mostly to ignore the headlines and ignore the propaganda. But, in just two years the terrorist organization carried out multiple attacks on the United States, which included the widely publicized beheading of US journalists James Foley and Steven Sotloff. These attacks impossible to ignore and left many people in fear. The United States doubled down with multiple air strikes and planted their feet firmly in Iraq and Syria against the Islamic State terrorist organization.

When I first learned about the project in Iraq, I felt confused. My initial reaction was clear and defined without knowing a single detail, but I had dozens of questions. Normally, upon learning about an international assignment with Nadus Films, I’m hit with tsunami of excitement, but this was different… I was scared.

Every meeting, phone conversation, text and email was held with the utmost discretion, we couldn’t tell our friends or families without severe delicacy. Over the course of one week, I learned about the project in detail and the people behind it.

Unseen is a non-profit 501(c)(3) which provides support for non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to grow. They offer marketing and fundraising to expand the NGO donor base. Nadus Films is a non-profit 501(c)(3) which offers storytelling through film and photography. In partnership Unseen and Nadus Films, our job was to support an NGO, who will remain anonymous, but will be called "Iraq Charity," led by Charlotte Hanson who provides humanitarian assistance in disaster relief and development situations.

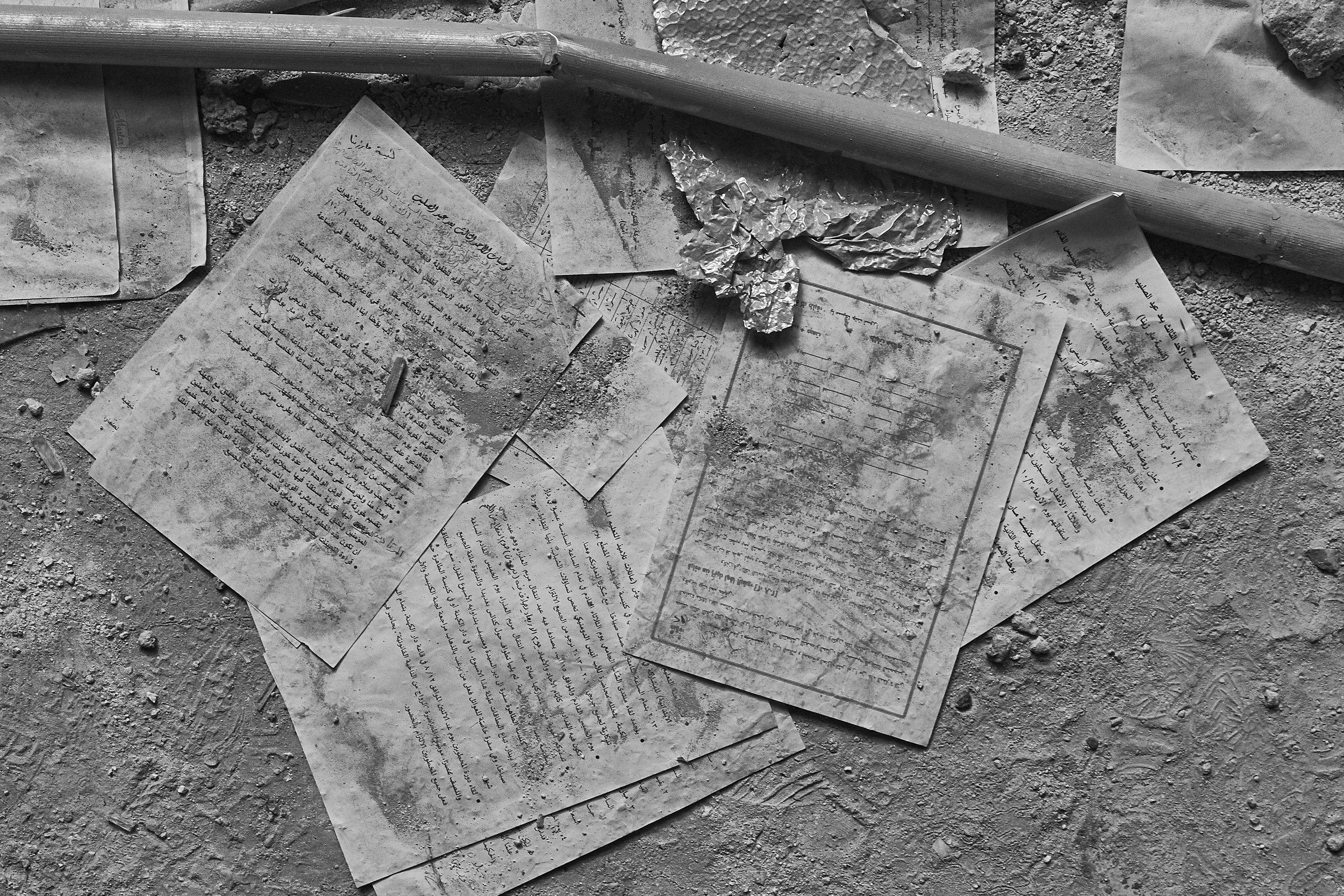

In August of 2014, ISIS militants swept through small cities near Mosul, Iraq forcing thousands of innocent people to flee overnight. Among those cities was Qaraqosh, Iraq’s largest Christian city with over 70,000 people. Over the course of two years, ISIS burned churches, destroyed icons and attempted to erase Christianity from Qaraqosh. Young women were put into sex slavery and young men were forced to carry suicide bombs. If they fought, they were tortured and killed.

In October of 2016, the Iraq Army, Peshmerga and the Nineveh Plains Forces pushed ISIS out of Qaraqosh, but all that remained was ruins; a city of ghosts. The homes were pillaged and burned and the people that were forced to flee overnight had been left with nothing. Today, Iraq Charity is gifting these persecuted people and providing them a chance to repair after ISIS. Our focus was to shed light on one of the thousands of families, who were finally returning to their war-torn home in Qaraqosh.

With the overview of the project in hand, logistics and security were our largest concern. After our own extensive research, there were so many questions, so many burdens, so many worries.

- What is the true situation in Mosul?

- Who would provide security on the ground?

- Who are our sources on the ground?

- What does our travel in Iraq look like?

- Where are we staying and for how long?

- Where are we most vulnerable in our travels?

- Are there IED’s present?

- What does our relationship look like with foreign military support while there?

- What would an evacuation plan look like?

As American “press” in the Middle East, we have a giant target attached to our back. But, as the answers flooding in, some of our concerns were eased while more concerns were raised. Naturally, the US Department of State stated extreme caution and advised that no American risk travel into Iraq. Kidnapping, sleeper cell suicide bombing and IED’s were all real threats. ISIS had been pushed back to the Syrian border in West Mosul and we would be working some 15 kilometers outside of East Mosul, but it felt to close for comfort.

We would fly from the United States into Erbil, Iraq situated an hour from Mosul and embed ourselves in Ankawa, the Christian community which sat just short drive from the US controlled airport in Erbil. Unfortunately, the more security we had, the more suspicion would be raised and the more likely we would be considered a target. We had to fly under the radar and blend in. Which was a hard pill to swallow.

We would have a total of three days on the ground, two of which would be spent in Qaraqosh. In order for the mission to be a success, it had to be very short and very hard, with long hours— a timeline Nadus Films and I were very familiar with. We wanted to get in and get the hell out.

While the project was a go, I was personally on the fence and only had three days to make a decision before the flight was booked. During the course of those 72 hours, I tossed and turned at night, had vivid dreams and battled an inner struggle of unease. I had a lot of emotional support from my close friends, but that didn’t calm my mind from moving a thousand miles per hour and dozens of random thoughts crossing my vision per second. One moment, I would convince myself that I couldn’t risk it. Then, I would sway to other side by persuading myself it would be a decision I would regret. Back and forth, back and forth.

One side was led by fear and the other side was led by determination. Questions were answered, but that didn’t stop my mind from wandering.

- Would this open new doors I don’t want?

- How will people react?

- How will I tell my family?

- Am I willing to risk my life for photography?

Coury Deeb, founder and director of Nadus Films, is one of the strongest men I know. Coury has led our team through the swamps and up mountains in dozens of war-torn, poverty-stricken countries all over the world. He has changed the world and he has certainly changed my world.

According to the Foreign & Commonwealth Office, Iraq is one of the most dangerous countries in the world. Therefore, this project was the mecca, an opportunity for Nadus Films to reach an entirely new level of donor base and that is something I couldn’t ignore. Coury’s confidence and calm demeanor throughout the pre-production is what kept me grounded and eventually helped me come to a decision.

Leading up to our decision deadline we had a series of meetings and conference calls. I was taking calls on other productions and on the road. It was discrete chaos, but needed. Our meetings included Nadus Films, Iraq Charity, Unseen and two military security advisors; Troy Wilson and Adam Brown. After every call, I either felt calm or anxiety. We walked through all of our questions, including what to wear, how to act, what to expect and where we would be.

At the end of the day, the biggest risk would not be kidnapping, snipers or terrorist action, it would be ourselves. It was important to stay calm in a hectic situation that was completely normal for the Iraqi people. I was confident we had traveled to enough third world countries to respect the process and remain calm in a tensioned zone. With every trip into Qaraqosh, we would face several Peshmerga checkpoints and being American, we would always have eyes on us.

All of our questions were heard and answered, we were going to Iraq.

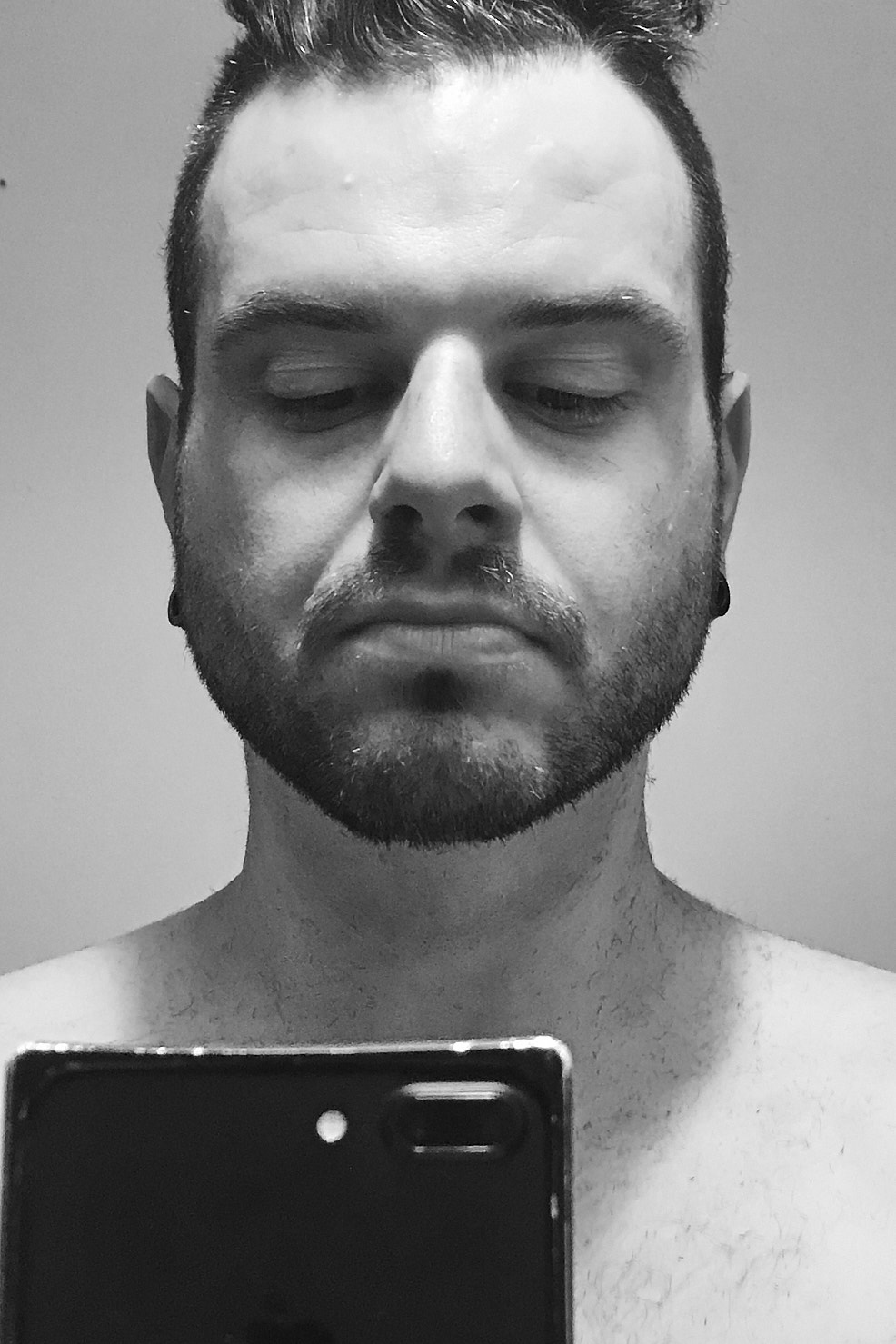

With the guidance of Troy Wilson, our military security advisor, we were instructed to start growing out our facial hair and start seeking clothing that would blend in. We couldn’t have anything the remotely looked “military” or “special forces” on our person. We were instructed to wear a tough tennis shoe, button up long-sleeved shirt, cheap sunglasses, blue jeans, with all bold colors and nothing flashy or tight-fitting. We would be recognized as a group of white Americans, but at least we wouldn’t be recognized as a threat.

The next objective was equipment. Due to the nature of airport security and checkpoint security we had to remain completely low-profile. No grip, no tripods, no stabilization, no battery packs and no cases. This meant shedding as much weight as possible and taking only the essentials, the bare bones, the smallest, most efficient camera system possible for both film and photography. We needed a workhorse that would have an extensive battery-life, the ability to withstand extreme weather and most importantly look “less-than-professional.”

After a series of meetings with Nadus Films, our Director of Photography, Drew Layman, decided it be best to use the most reliable camera we know, the Canon 5D Mark IV. But, with video we needed something to stabilize the body and add additional points of contact. Drew suggested the Zacuto Enforcer, a highly portable shoulder mount with a foldable design that makes it ideal for our run-and-gun documentary style. Also, knowing we’d be out in the broad desert daylight we would need the Zacuto Z-Finder Pro Optical Viewfinder. Then, finally we would use the Rode VideoMic Pro to record any sound beyond our wireless lavalier microphone systems.

As far as lenses, we wanted just about every focal length possible. I would solely use the Canon EF ‑ 24mm‑70mm ‑ F/2.8L, while the motion side would rely on the Canon EF ‑ 24mm‑105mm ‑ F/4L, the Canon EF ‑ 16-35mm ‑ F/2.8L and the Canon EF ‑ 70mm‑200mm ‑ F/2.8L. We would also carry a Singh-Ray Variable Neutral Density Filter and Hoya Polarization Filter for each lens.

Once our equipment list was in place, I called upon my friends at Canon and BorrowLenses, who were gracious enough to support the project and provide all the tools we needed.

The largest hurdle for Nadus Films was the drone, we needed arial footage, but Iraq is a no-fly zone. ISIS and other militia use drones to scout and create strategies. DJI claims its impossible to fly, but we researched otherwise. We had to be extremely careful. So, we purchased the new DJI Mavic Pro; a light-weight, pocket-sized drone with a Gimbal-Stabilized 12MP/4K Camera. It was small, powerful and ideal for quick aerial photography. It would be a giant risk, one we were willing to take.

The largest hurdle for still photography was lighting. Despite it's small footprint in the photo world, the Profoto B2 system was out. The battery pack and head just attract too much attention, instead I opted for a simple Canon 600EX II-RT speedlight. I needed a very small, soft modifier and a very small monopod. MeFoto had just introduced the Walkabout Air 6-section monopod, which measures only 13 inches when closed; exactly the portability I needed. With only two days before our flight, I still needed a modifier that was small enough to fit in a backpack. So, I called upon my friends at Profoto for the smallest umbrella they create; the 33” Shallow White Umbrella with diffusion. Once it arrived, I sawed off the center shaft, gaffed the umbrella tips and clipped the diffusion to the umbrella. It was perfect.

Despite the equipment locked in, we still had to figure our the best method to pack it all, in several low-profile backpacks that we could carry-on through the airport and on the plane. I normally will pack everything into a Think Tank Photo Airport International V2, but now I had to fit everything into a logo-less Swiss Army backpack. I lined the backpack with velcro and placed inserts to guarantee all the camera equipment would remain secure. Then, filled the other pockets with a laptop, accessories, clothes, toiletries, supplements and green tea. Once it was packed, I could barley fit a quarter.

Our last conference call was stressful. We went over travel details, timelines, security issues and updated ISIS press. Nerves were at an all time high, but I had to trust the team and trust the process. We had to file documents with the US Department Of State, complete medical evacuation insurance documents and provide emergency details, including blood type. I printed and laminated copies of my Passport and placed them in several locations, including the bottom of my right shoe. No detail was overlooked, we had to be prepared for action.

The night before the flight was surprisingly calm. I did sleep, but it was restless. Luckily, I have an awesome, supporting partner who remained strong herself, kept me cool and reminded me to breathe. Emotions were high, but I felt as prepared and ready as I could ever be. At 10:00 a.m. the next morning, I arrived at the Nadus Films office to go over any last minute strategies and equipment. All of our spirits were high and we were prepared for the long trip into the Middle East. We said an intense prayer and headed to the airport. There was no turning back.

We met our personal security advisor, Troy Wilson and Unseen producer, Melanie Iverson in Chicago before we jumped on a plane into Vienna. Although, I felt safe with an additional set of eyes on our back, the anticipation of the unknown was what terrified me the most.

The flight into Vienna was long, but standard. Fortunately, I had downloaded the entire Netflix series “Narcos” and binged watched the first season, which made the flight a breeze. Upon landing in Vienna, we were met by Iraq Charity founder, Charlotte Hanson. Charlotte was strong, determined and had all the attributes of a natural born leader. She spoke in a serene South African accent, which could calm the nerves of anyone in conversation. She was our guiding light and had all the resources we needed on the ground for a successful project.

Although, this was in our package of initial questions, I didn’t know what to expect on the flight from Vienna to Erbil, Iraq. But, come to find out, it was perfectly normal. Mostly empty, the flight consisted of a few Iraqi and a few brave travelers doing business or humanitarian aid. I also noticed a one additional American on the flight; likely military. The camouflage backpack with a “Make Mosul Great Again” patch, gave it away.

I had prepared myself mentally for this trip for over three weeks and had run every scenario through my head upon landing in Iraq. What to say, how to act and how to handle customs. We stepped out of the plane into the dry-hot air and walked into the airport to customs. At first glance, the airport was nice, but relatively empty. There wasn’t many people who traveled in and out of Iraq, obviously. We passed through customs without a single question and picked up our baggage. We then passed through a security checkpoint with prevail.

Once through the airport we were met by two Iraqi men, Rauf and Jamir. Jamir had military fatigues and was apart of the Nineveh Plains Forces, who would act as our eyes on the ground. While Rauf wore plain clothes and represented the local television station. Rauf would also be our ears on the ground and our Arabic translator. He spoke good English and we immediately knew he was the man. Rauf had insane combat experience, blended with an incredibly kind soul who cared about his people. We jumped into two trucks and headed to our home base in Ankawa, the Christian quarter of Erbil, Iraq

I felt safe and I felt guarded. Our team on the ground was heavily connected and knew how important this project was to the Christian people of Iraq. Within minutes of arrival, we settled into our dorm-like rooms and began to break out equipment and prepare for the first evening of production. The people in our residence were extremely kind and prepared our first meal in the Middle East. It was incredible; lamb and chicken kabobs with fresh pickled vegetables and hummus.

Our mission of the evening would be to capture the people forced into IDP Camps. Camps that were setup by UNHCR, UNICEF or NGOs to provide shelter for those families displaced by ISIS takeover or military action. As of 2017, over three million Iraqi people have been displaced, a vast majority living in temporary camps. Due to ISIS liberation, they are slowly returning home.

I didn’t know what to expect, but upon arrival we were greeted with open arms and welcomed into the community. Children were everywhere, small stores were established and it seemed like people were thriving despite the horrific situation. I went into work-mode and began firing on all cylinders. I wanted to be as candid as possible, so I set the Canon 5D Mark IV to "Silent Mode" and hugged the walls to stay out of sight, while the film crew carried out their shots. The children were enthralled with the camera lens, but they actually knew what it was compared to other third world countries we’ve visited. They smiled, laughed and played while we documented. Smartphone selfies seemed to be a popular thing, especially among the teenagers. So, we just went with it.

We followed the lead of Rauf, while Troy and Jamir were at our sides watching the environment for the smallest disturbance. Within two hours we had captured a worship service, the people and plenty of the camp to go along with it. It felt warm and content, despite the dark overtone of it all. We returned to our home base thrilled with the photography of the first day, but on edge for the day to come. We ended the day meeting the family who was to be our focus for the documentary. We walked into a triple story apartment, in which three families were currently living after being pushed out of Qaraqosh. They were all related. The family consisted of several brothers who owned and operated a mechanic shop in Qaraqosh, they would be a vital element to the story. Charolette had gifted them a grant to rebuild their business, with new equipment and tools. We would get started early and document their return to Qaraqosh.

I was exhausted. I had barley slept in over 24 hours and I did my best to stay alert for the de-briefing and dinner, but was ready to get rest.

I awoke early to a chilled air-conditioned room, the bright sun peaking through the transparent shades, fully-rested and ready to take on the day. Nerves were high, as our first day into Qaraqosh happened to be on the Islam holiday Ramadan, a day which Islamic terrorist attacks are called to action. But, we all swallowed the tension and prepared for trek through Kurdistan. Our day started at a mechanic equipment retailer outside of Erbil, where the brothers had to pick up their brand new tools to transport into Qaraqosh. In any country where English isn’t the native language it’s tough to know what is really going on. You have to read body language. But in Iraq, loud confusion seemed to be the normal.

Once the brothers had double checked their order and loaded the truck, we were on our way to Qaraqosh. Within a few minutes, we were met by Jamir and a truckload of Nineveh Plains Forces. I’m sure an American film crew isn’t on the Nineveh Plains Forces priority list, but we all gave into the sense of security they offered. If there was a threat, they would be the first to know it. We pulled into our first checkpoint and passed through without a single issue. Due to Ramadan, there weren’t many people on the roads. As we inched closer and closer to Mosul, the dismal brown landscape became more and more war-torn. Shattered structures, black grass, covered fox holes and old concrete barriers. You could feel it in the air, something horrid had taken place. We passed through two more checkpoints without an issue. Apparently, Rauf and Jamir has alerted the Peshmerga that we would be traveling through, therefore the conversation remained calm and collected. I often would hear “Amrikiyyan” from Rauf’s mouth, which would usually allow us a quick pass. Apparently, for decades the United States has supported Peshmerga with training, artillery and weaponry. Therefore they are friendly to American people traveling in Iraq. As a matter of fact, we’d occasionally see a Peshmerga soldier in United States military uniform.

Our second to last checkpoint was the most difficult. We were asked to get out of the vehicle and show our passports. Although, completely routine, it was nerve-racking to not know what was going on or what the soldiers were discussing behind the vehicle, but we trusted Rauf and Jamir. Nevertheless, after a quick passport check, we were on our way. I silently took a deep breath.

We arrived into Qaraqosh after about an hour and half. As we entered, we hit a roundabout where a giant cross had been planted and never uprooted. I expected a small desert town and what I saw was semi-large city, completely void of life. It looked abandoned, but forcefully destroyed. The ground was crusted with ash and overgrown from weeds. The homes were tarnished in black from fire and ransacked of all valuable belongings. Businesses were laced with artillery and painted with ISIS propaganda. Churches were even worse. On occasion we would see a person sweeping up their sidewalk or a car circling the block but, it was a ghost city. We arrived to our destination on the outskirts of the city, where the brothers operated their business.

During our initial security briefing we were told to not venture into random spaces, open fields or touch anything out of place due to landmines and traps. My plan was to stick close to everyone and do my best to get what I needed, but I wasn’t used to this process. Normally, I take the liberty to explore the location and find the composition I need. Once we had our feet on the ground, I felt confident to walk around carefully away from the crew, but within an ear shot.

While the brothers began to setup their shop and unpackaged all their new equipment, we got to work. While most of the shots were organic documentation, others had to be planned and setup for success. It was all moving slow, but details were important.

While the team worked, I made sure to capture a few photographs of the Nineveh Plains Forces soldiers that were our acting security. In full battle uniform and hands-on their AK-47 semi-automatic machine guns, they just loved the camera. They had no problem posing for the perfect shot, which also included a few selfies. Unfortunately, I didn’t have time to bring in the artificial lighting, but suspected they would be back again the following day. They did not return.

Once we felt confident in the content we were capturing, Coury decided to take the drone on a quick test run and without a hitch the drone lifted off with full GPS control, a giant relief. While Coury piloted the drone over the city, I began to setup for the portrait session of the brothers.

My setup consisted of a MeFoto Walkabout Air Monopod which attached to a Tether Tools RapidMount Cold Shoe Elbow Mount which supported a Canon 600EX II-RT speedlight modified by a 33” Shallow White Umbrella with an outer diffusion baffle. After some confusion with one of the brothers, we jumped right into it. Portrait after portrait I was nailing dramatic and engaging portraits that told a story. I didn’t need to talk, I just let each of the men consume the moment and be photographed, with the occasional slight direction. But, like many of our other projects, I didn’t have much time. After 20 minutes, which seemed like 2 minutes, the brothers were done a ready to head home.

Many Iraqi people have suffered tremendous trauma and suffer from PTSD. This was a sensitive topic, so we had to tread lightly and not push the emotion. We packed up before sunset and headed back towards the center of the city. We stopped off at a church that had been completely destroyed. Statues of Jesus Christ had all been beheaded and paintings had been shred of the faces. It was a somber and compelling moment that left us all speechless. After the church tour, we jumped into the van and headed back into Erbil through the numerous checkpoints without an issue.

That evening was interesting. While I won’t go into detail, I will say that we had an interview with a general and a politician, which ended on a sour note. But, if there was one take away from that evening, it was where I started to see all the real complexities of the Middle East.

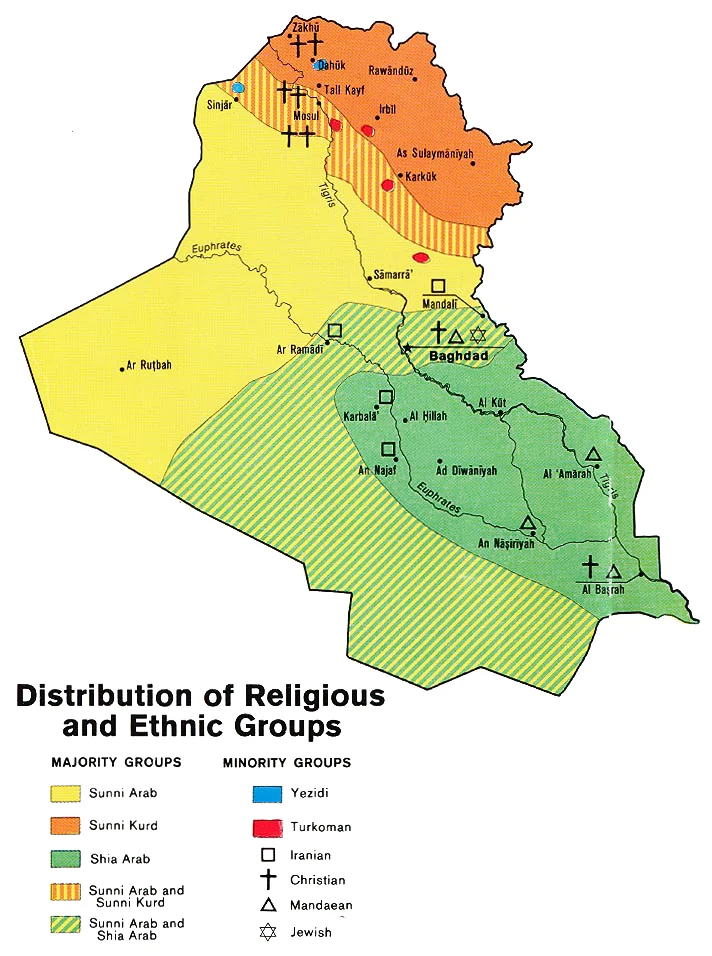

It's not black and white, which is what the people of the United States are spoon-fed everyday. Iraq, otherwise known as the "Axis Of Evil," consists of over 35 million everyday, warm people which are usually left in the cold in the eyes of the western world. I had no idea how many religious communities, organizations, militias and regions there are. It’s an anti-melting pot of confusion, that only few people can truly understand.

- There are four main religious communities; Shia Islam, Sunni Islam, Yazdanism and Christianity.

- There are two main ethnic groups; Kurdish and Arabic.

- There is Jihadism. Jihadists are often Sunni extremists perceived as a military movement, such as al-Qaeda and Islamic State(ISIS). They see the violent struggle as necessary to eradicate all other religion and defend the Muslim community.

There are Kurdish Shia and there are Arab Shia. They don’t like each other. There are Kurdish Sunni and there are Kurdish Yazidi. They don’t like each other. There are Arab Yazidi and there are Arab Christian. They are the minority.

Among each of these ethnic groups and religious communities are dozens of paramilitaries and militias fighting against Jihadism for peace, land and power. While most of these communities strive for peace, some cannot accept a person of different religion or ethnicity, which often will result in violence.

So, just imagine your neighbor disliking you for only your religion, while you share the same ethnicity. On the flip-side, perhaps they dislike you for just your ethnicity, yet you share the same religion. But, your neighbor's son, dislikes both your religion and your ethnicity, so much so, he would be willing to hurt you if you don’t convert to his religion. Then, your neighbor’s cousin down the street likes your neighbor’s son, but dislikes his father for the way he prays. You and the son are just collateral damage.

It all sounds like the Wild Wild West, right? Well, It's complicated.

I woke up the next day with a headache. I felt tired and beaten down. I haven’t shaved in over a month and I haven’t showered since leaving Louisville. The United States military uses a term for pressing through hardship, which I stand by on every tough project on foreign ground; “Embrace The Suck.” I had to constantly pinch and remind myself that we were in Iraq, the most dangerous country in the world. The gesture brought my head to level ground and forced me to tie my shoes tighter than normal. We all had to put aside normal comforts for safety and time.

Our second day in Qaraqosh began early. The air was thick with emotion that weighed heavy on our hearts. It was a day that we truly had to be candid and treat the situation with the utmost respect. The family of women and children had not seen their home since that frightful night where they all evacuated their homes in the middle of the night to evade ISIS. We expected the home to be ravaged and destroyed, so it all had to be captured in sensitivity. We were used to warmth and sympathy in foreign countries, but never to this level of intensity.

The family traveled through all the checkpoints in one large van, while we followed in a SUV not far behind. Occasionally, we would pass the van to capture the children peering through the windows or the women silently praying. Fortunately, Rauf and Jamir talked their way through all the Kurdish checkpoints and we finally made it into Bakhdida.

As the family entered their home for the first time, we all began to feel the emotional burden. The only thing that could be heard was the children quietly playing throughout the house. The house had been trashed and only a few family remnants remained. All their pictures had been destroyed and all of their Christian relics had been beheaded or torn. The men didn’t hesitate to start the clean-up, while the women slowly paced around each room gathering tarnished heirlooms and dusting off the ash.

It was a moment that will always remain with me and close to my heart. The pain was silent but could be felt in the room. When the women paused, I paused and respected their silence by refraining from the shutter. Even with a silent shutter, the sound of my camera felt like a gun shot that reverberated throughout the room. So, I creeped around corners, remained low to the ground and hugged the cracked walls to do my best to remain out of sight and out of mind.

After a short time, I headed back out of the house with our private security Troy and scouted the exterior of the house as well as the entire block. The house next door had been completely demolished with a missile air strike and the business next door to that had been destroyed by a suicide bomber, who had used an armored truck as the delivery device. Adjacent to that business was a ground level operation ISIS had created to manufacturer improvised explosive devices otherwise known as IEDs. It was an aftermath of war and this family was situated directly in the middle of it all. Fortunately, there was no sign of life, anywhere.

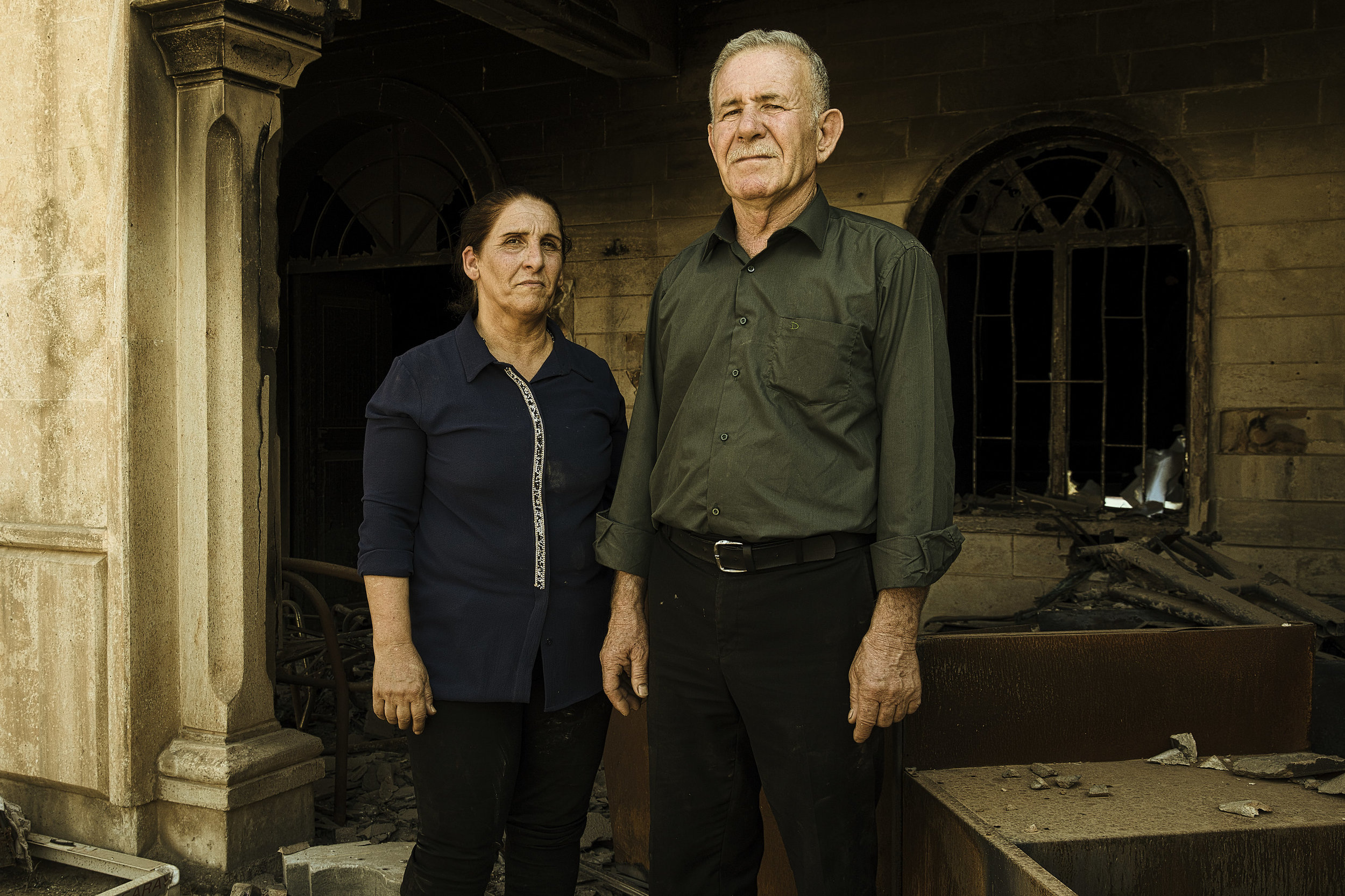

It truly felt like a city of ghosts. Troy and I wandered back around the home to find a church courtyard connected to the back gate. The exterior had been charred black with fire and it smelled of death. A dried dog carcass sat parallel to a fire pit surrounded by artillery shells and trash from what looked like a sobering celebration. As we entered the church, we were hit with a distinct air that felt thick of charcoal and synthetics. ISIS had attempted to destroy the entire sanctuary with C-4 and burn the rest. We had to tread lightly, but I knew this would be an incredible location for a series of portraits. I loved the juxtaposition of this incredibly strong family, placed in a torn environment on the very day of their return to the city. The message symbolized a reckoning and a stand. It was powerful.

After an amazing lunch prepared by the family, we headed to the roof of the church where the brothers would repair and re-construct the cross that had fallen on the dome of the church while the rest of the family watched from the roof of their home. Within moments, the brothers had lifted and re-positioned the steel-beam cross upright and anchored the base with large cinder blocks. The family chanted and prayed while I frantically sprayed the shutter in every direction for the best shot.

I took a deep breath and prepared the for final stage of portraits. I was given a bright sun and had to do my best without any diffusion whatsoever. We couldn’t shoot inside the church, because the family didn’t want the children to be anywhere near the airborne C-4 by-product. So, I instinctively headed for the open shade at the front of the church where there was plenty of burnt chairs, tables and props to be used as foundational elements for staging and posing.

The families all gathered for a quick group portrait. I knew that they had lost everything, including all of their family pictures, so it was important for me to capture these images in a light-tone, simple, natural light and nothing too dramatic. Although, there was a dark undertone, due to the blackened church background, the mood was happy. They were finally making the first step to rebuild. Once the family portraits were complete, we knocked out a few individuals including the mother, Jamir and of course a group portrait of the documentary crew. It’s always a relief to finish the most difficult part of my job, especially under such extreme pressure and circumstances but I’m usually left wanting more or better. I guess you could say I’m my own worst critic.

While the family packed and headed out of Bakhdida, we opted to stay later for a candid interview with Charlotte, the founder of Iraq Charity. I took the time to explore the surrounding area as safely as possible and capture more rooftop imagery. Alone, I remember it being a moment of solace and reflection. Roughly an hour later, we jumped in the van to exit Bakhdida for the final time. Our last stop was the large community church, where we closed the project with a quick portrait of Charlotte, the last piece of the puzzle.

One comforting security condition of this project, was that the United States military still had a strong presence in the area. If we felt any threat, we had contingency plans to be evacuated immediately. Even though we didn't see one single soldier, the presence was intimidating.

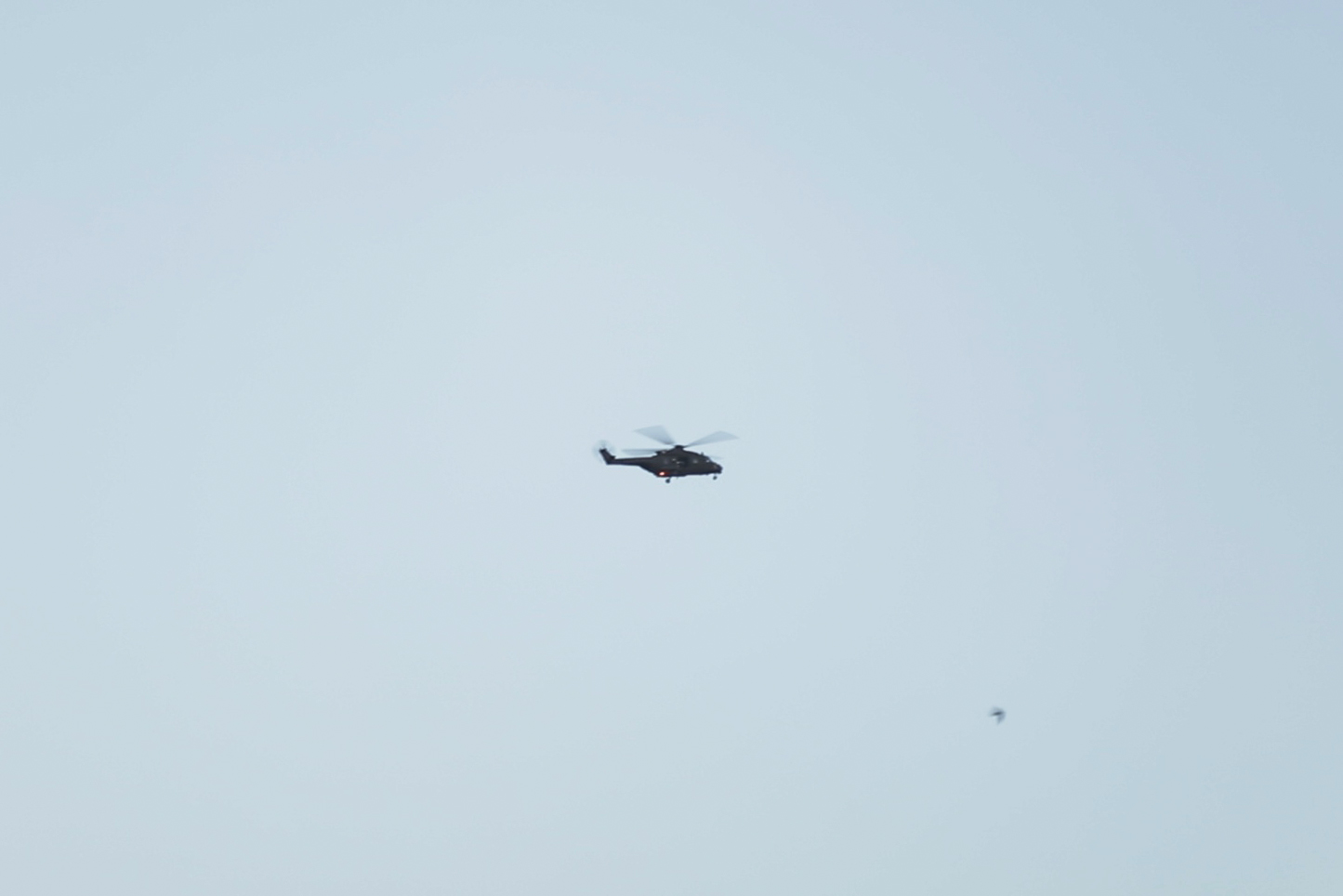

Before we headed out to dinner, we setup on the rooftop of our home base to capture a few timelapses of the sunset. Then slowly two four-bladed, twin-engine Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters came into vision from behind. We knew they were heading into the airport to the west, but didn't expect them to take a double pass and circle around the rooftop. We knew they knew an American crew was there, we were just not sure if they could pinpoint it was us or what we were doing. My heart sank for 60 seconds, but we stood our ground and filmed the moment in its entirety. The only time I truly felt a primal concern during my time in Iraq was from the military of my own country.

It wouldn’t be a solid trip if weren’t able to visit some of the local scene, so after the sunset scare we headed our for celebratory food and drinks. While we remained in Ankawa, the Christian quarter of Erbil, Iraq, we walked into a large courtyard packed with dozens of long plastic patio furniture and a live band. As many people arm themselves in Iraq, all firearms had to be checked at the door. The environment was happy, people were cheering, dancing and laughing. We were in Iraq, but we all felt safe. As tradition in foreign countries, we ordered several hookahs, a lot of random appetizers and a lot of beer. It put a large smile on my face to see these people who are under so must strain just relax and have fun. After dozens of drinks and tons of amazing Middle Eastern food, we left the courtyard at closing time. It was the relief we needed before we wrapped the project.

Sunrise hit hard. We all felt rough as we headed into our last full day in Iraq. Our last day focused on the Dominican Sisters and their impact on Iraqi people that have been displaced from the military movement of ISIS. With the help of Charlotte Hanson, the Dominican Sisters have rebuilt schools, businesses and churches. They are slowly making progress in Erbil and surrounding Christian cities. They are also providing on the ground support to IDP camps around Mosul where the United Nations has has failed.

After we documented the Dominican Sisters and the their effort to help innocent families with Iraq Charity, we opted to head out to the Dayro d-Mor Mattaia monastery, which dates back to roughly 363 A.D. The historic monastery is located atop Mount Alfaf in northern Iraq and is less than 12 miles from Mosul. It is recognized as one of the oldest Christian monasteries in existence. Shadows from the sun created beautiful parallel lines and strong contrast which only added to the overwhelming power of the warm stone facade. We explored every corner and opened every unlocked door, but after an hour we had to get moving and beat the sunset back to Erbil.

The day ended with an incredible dinner at the home of our focus family. As we wrapped our meal in prayer and goodbyes, I handed them prints of the family portraits I snapped the previous day in Qaraqosh. It was a beautiful moment that I owe to Charlotte who devised the gift from the start and worked to have the prints made locally. Although the evening was bittersweet, we were all ready to leave Iraq and get to United States sovereign ground. We spent several hours making sure our backpacks were underweight and the footage was backed up and stored with several different people.

Our exit from Erbil, Iraq to Frankfurt, Germany was interesting. The six security checkpoints, including customs was nerve-wracking. But, despite the odds we made it through the tight security and on the plane with all of our equipment and hard drives.

As the wheels lifting off the ground, I took a deep breath and a wave of anxiety lifted from my shoulders, we did it. I nearly kissed the ground as we walked down the tarmac in Frankfurt. The weather was hot and slightly humid, but that didn’t stop us from immediately heading to the nearest beer hall to celebrate the successful trip into one of the most dangerous places on earth.

Similar to most of our international projects, there was an intense adjustment period of settling back into the comfort of my home. The shower and fresh shave pushed the process, but the sheer exhaustion caught up with my body and I came down with an stomach sickness, which required two weeks to recover.

The complexities of Iraq was eye-opening, like a dark red curtain pulled-back. I can only hope our project makes an impact and pierces through the black cloud of faulty perception we may have of these 35 million innocent people, who are struggling to restore their lives after so much war and terror.

Fear has a direct control over many aspects of our every day life and I’ve always preached the larger the risk the larger the reward. I believe that conquering fear only makes us stronger. In the end, the only regret will be the risk you didn't take.